Chain of Responsibility Pattern

“Avoid coupling the sender of a request to its receiver by giving more than one object a chance to handle the request. Chain the receiving objects and pass the request along the chain until an object handles it.”

Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software

The Chain of Responsibility pattern is part of the classic Gang of Four behavior pattern family that addresses responsibilities of objects in an application and how they communicate between them.

The entire family of behavior patterns revolves around the principle of “object composition rather than inheritance”. This principle is currently been widely adopted by the developer community because of the benefits it offers. What this principle states is – instead of extending from an existing class, design your class to refer an existing class that you want to use. In Java, it’s done by declaring an instance variable referencing the object of the existing class. Then, by initializing the object either through the constructor or a method, and finally using the referred (composed) object.

Chain of Responsibility Pattern: Introduction

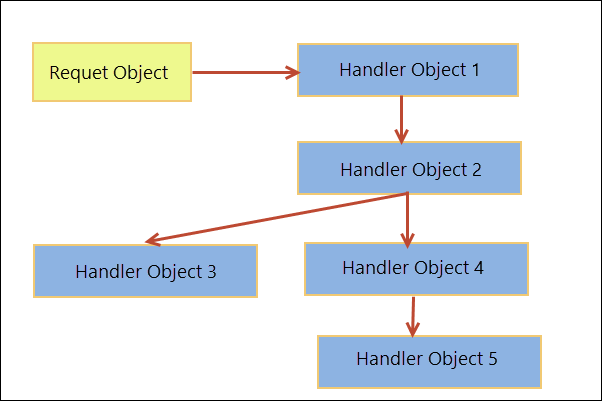

The Chain of Responsibility pattern is easy to understand and apply. In applications there is always a client that initiates a request and an application object that handles it.

What the Chain of Responsibility pattern states is – decouple the client who sends the request to the object that handles it. The solution is a list of handler objects, also known as responding objects each capable to deal with a specific nature of request. If one handler object can’t handle a request, it passes it to the next object in the chain. At the end of the chain, there will be one or more generic handler objects implementing default behavior for the request.

You can relate the Chain of Responsibility pattern with a Customer Service technical help desk that you call up with a technical query/help for some product or service (think yourself as a request object). A technical help desk executive tries to resolve it (Think in terms of objects – the first object in the chain). If they can’t resolve it – maybe for some billing related issues, it moves to a billing help desk executive (the second object). If the billing help desk can’t resolve either, your request goes to the general help desk (the third object), and so on – until someone handles your request.

Participants of the Chain of Responsibility Pattern

Continuing with the Customer Service help desk example, let’s model it in terms of a Java program. We create an abstract class- AbstractSupportHandler. This class will assign request levels and delegate to the different Customer Service handlers. This class will also manage when a specific request level of a customer can’t’ be handled by a request handler. Then, the request will be delegated to the next handler on the line.

For each specific handler, we will model specific classes extending AbstractSupportHandler. Let’s name them TechnicalSupportHandler, BillingSupportHandler, and finally GeneralSupportHandler.

It will be a RequestorClient class that will initiate a request for the handlers to process.

A classic example of the Dependency Inversion Principle that states: Modules should be independent. They should depend on abstractions. and abstractions should not depend on details. Details should depend on abstractions. Our object chain depends on the abstraction (AbstractSupportHandler)

On the context of the Customer Service help desk example, the participants of the Chain of Responsibility pattern are:

- Handler (

AbstractSupportHandler) Abstract base class acting as the interface to handle request. Optionally, but most often the Handler implements the chain links. - ConcreteHandler (

TechnicalSupportHandler,BillingSupportHandler, andGeneralSupportHandler.) Handles request, else passes it to the next successor of the handler chain - Client(

RequestorClient): Initiates a request that one of the chain of handlers ( a ConcreteHandler) handles

Applying the Chain of Responsibility Pattern

Moving ahead with our Customer Service help desk example, let’s write the AbstractSupportHandler class – the Handler.

AbstractSupportHandler.java

//404: Not Found

In the class above, we first assigned levels to constant variables that represents the type of client requests from Line-5 to Line-7. We then wrote a setNextHandler() method in Line- 12 to Line -14 that will get called to use the next handler in the chain. The receiveRequest() from Line-16 to Line-23 is where the passing of a client’s request in the object’s chain occur. In this method, we first checked whether the initial object on the chain can handle the request. If so, we called the handleRequest() method that we declared as abstract. Else, we sent the control back to receiveRequest(). Next, we will write the ConcreteHandler classes. Each of them extends AbstractSupportHandler and implements the handleRequest() method. Also note that each of the ConcreteHandler classes are initialized with their levels declared as constant variables in the abstract AbstractSupportHandler super class.

TechnicalSupportHandler.java

//package guru.springframework.gof.ChainofResponsibility.handlers;

public class TechnicalSupportHandler extends AbstractSupportHandler {

public TechnicalSupportHandler(int level){

this.level = level;

}

@Override

protected void handleRequest(String message) {

System.out.println("TechnicalSupportHandler: Processing request " + message);

}

}

BillingSupportHandler.java

//package guru.springframework.gof.ChainofResponsibility.handlers;

public class BillingSupportHandler extends AbstractSupportHandler {

public BillingSupportHandler(int level){

this.level = level;

}

@Override

protected void handleRequest (String message){

System.out.println("BillingSupportHandler: Processing request. " + message);

}

}

GeneralSupportHandler.java

//404: Not Found

Let’s now write the client.

RequestorClient.java

//package guru.springframework.gof.ChainofResponsibility;

import guru.springframework.gof.ChainofResponsibility.handlers.BillingSupportHandler;

import guru.springframework.gof.ChainofResponsibility.handlers.AbstractSupportHandler;

import guru.springframework.gof.ChainofResponsibility.handlers.GeneralSupportHandler;

import guru.springframework.gof.ChainofResponsibility.handlers.TechnicalSupportHandler;

public class RequestorClient {

public static AbstractSupportHandler getHandlerChain(){

AbstractSupportHandler technicalSupportHandler = new TechnicalSupportHandler( AbstractSupportHandler.TECHNICAL);

AbstractSupportHandler billingSupportHandler = new BillingSupportHandler( AbstractSupportHandler.BILLING);

AbstractSupportHandler generalSupportHandler = new GeneralSupportHandler(AbstractSupportHandler.GENERAL);

technicalSupportHandler.setNextHandler(billingSupportHandler);

billingSupportHandler.setNextHandler(generalSupportHandler);

return technicalSupportHandler;

}

}

In the client class, we wrote a getHandlerChain() method that returns a AbstractSupportHandler object. In this method, we started by instantiating the ConcreteHandler: TechnicalSupportHandler, BillingSupportHandler, and GeneralSupportHandler. In this method we set up and returned the handler chain. To see how the Chain of Responsibility pattern work, we will write some test code.

RequestorClientTest.java

//package guru.springframework.gof.ChainofResponsibility;

import guru.springframework.gof.ChainofResponsibility.handlers.AbstractSupportHandler;

import org.junit.Test;

import static org.junit.Assert.*;

public class RequestorClientTest {

@Test

public void testGetHandlerChain() throws Exception {

AbstractSupportHandler handler=RequestorClient.getHandlerChain();

handler.receiveRequest(AbstractSupportHandler.TECHNICAL, " I'm having problem with my internet connectivity.");

System.out.println("............................................");

handler.receiveRequest(AbstractSupportHandler.BILLING, "Please resend my bill of this month.");

System.out.println("............................................");

handler.receiveRequest(AbstractSupportHandler.GENERAL, "Please send any other plans for home users.");

}

}

The output is this.

------------------------------------------------------- T E S T S ------------------------------------------------------- Running guru.springframework.gof.ChainofResponsibility.RequestorClientTest TechnicalSupportHandler: Processing request I’m having problem with my internet connectivity. ............................................ TechnicalSupportHandler: Processing request Please resend my bill of this month. BillingSupportHandler: Processing request. Please resend my bill of this month. ............................................ TechnicalSupportHandler: Processing request Please send any other plans for home users. BillingSupportHandler: Processing request. Please send any other plans for home users. GeneralSupportHandler: Processing request. Please send any other plans for home users. Tests run: 1, Failures: 0, Errors: 0, Skipped: 0, Time elapsed: 0.055 sec - in guru.springframework.gof.ChainofResponsibility.RequestorClientTest

Summary

What I like about the Chain of Responsibility pattern is the complete decoupling between the client and the object chain that handles the client’s request.

In this pattern, the first object in the chain receives the client request. It either handles it or forwards it to the next object in the chain. The process goes on until some object in the chain handles the request. What’s interesting here is that the client that made the request has no explicit knowledge of who will handle the request. Also, the object who finally handles the request has no knowledge about the client who initiated the request.

This pattern is a classic implementation of the SOLID Principles Of Object Oriented Programming. I previously mentioned how the Dependency Inversion Principle applies in this design pattern. We also have the Single Responsibility Principle which states- The classes you write, should not be a swiss army knife. They should do one thing, and to that one thing well. In this example, we wrote the TechnicalSupportHandler,BillingSupportHandler, and GeneralSupportHandler classes. Each class is written for a single specific purpose. The Open Closed Principle states: “software entities (classes, modules, functions, etc.) should be fixed and yet represent an unbounded group of possible behaviors through concrete subclasses. Thus in this example, the abstract (AbstractSupportHandler) class and the concrete subclasses.

You will see the Chain of Responsibility pattern applied in the Spring Security project of the Spring Framework. In Spring Security for authentication and authorization you have chains of ‘voters’. This is highly configurable. This is what allows Spring Security to be so flexible when applied to enterprise application development. You can add voters for things like database authentication, or LDAP authentication. And it’s easy to add your own custom voters because of how the Chain of Responsibility Design pattern has been applied.

Mark

Hi! Your code preview is yielding a 404 error – just wanted to flag this. Thank you!

jt

Thanks – I changed syntax highlighting plugins & still working through older posts.

Miguel

Hello, there are still 2 blocks of code that show 404 error, they are accessible through the webarchive link that Martin provided though.

Martin

As a temporary solution, go check this post on waybackmachine.org snapshot

https://web.archive.org/web/20190410150703/http://springframework.guru/gang-of-four-design-patterns/chain-of-responsibility-pattern/

Victor

I believe your implementation for the receiveRequest method is not correct because, currently, all 3 of the SupportHandlers receive a call to handle the request. I believe the implementation should be modified so that they only handle a request of their level or *else* pass the responsibility to a lower SupportHandler.

Anyway, for the articles on Design Patterns.

Justine Carlos

Hi the AbstractSupportHandler.java part display 404 error.

bob Posert

Thanks for this! There’s a typo in the diagram “requet” object.