State Pattern

“Allow an object to alter its behavior when its internal state changes. The object will appear to change its class.”

Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software

In the series of the Gang of Four design patterns, I wrote about the Command, Chain of Responsibility, Iterator, Mediator, Interpreter, Memento, and Observer patterns. These are part of the Behavioral pattern family that address responsibilities of objects in an application and how they communicate between them at runtime. In this post, I will discuss about the State Pattern – an important pattern that allows an object to change its behavior when it’s internal state changes. The State Pattern implements the Open Closed and Single Responsibility principles that are part of the SOLID design principles.

State Pattern: Introduction

In enterprise applications, some domain objects have a concept of state. Behavior of domain object (how it responds to business methods) depends on its state, and business methods may change the state forcing the object to behave differently after being invoked. The State Pattern encapsulates state of such domain object into separate classes and at runtime delegates to the object representing the current state – through what we know as polymorphism.

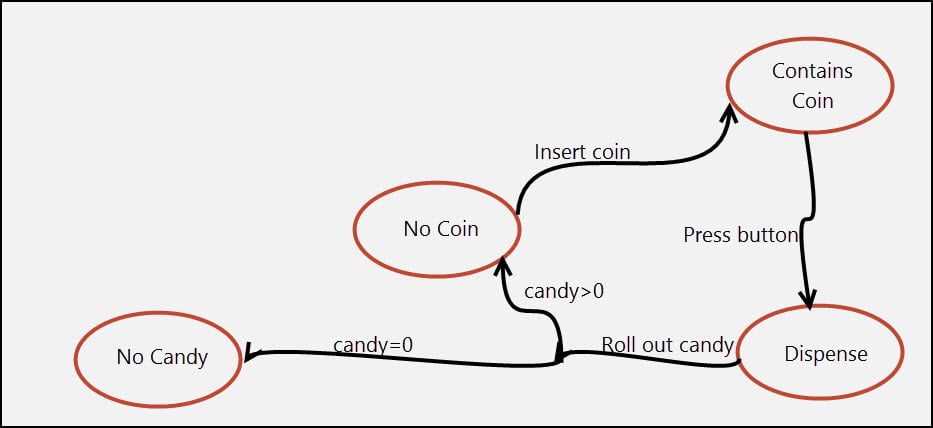

The best way to understand the State pattern is by an example. Let’s examine the State pattern through a candy vending machine example. The requirement of the vending machine is to roll out a candy whenever a user inserts a coin into the machine and presses a button. From this requirement, we can see that the machine will have four states: No Coin, Contains Coin, Dispense, and No Candy. These states represent different behavior of the machine. State transitions will move the machine from one state to another. As an example, if the current state of the machine is No Coin, and then a user enters a coin, a state transition will move the machine to the Contains Coin state. Here is how the state diagram of the candy vending machine looks like.

In the figure above, the red circles represents the states of the machine and the arrows the state transitions.

As a programmer, if you are asked to write the code for the candy vending machine, you probably think it should be simple. And yes, it is a simple task. We could have a single CandyVendingMachine class. The class can have instance variables to represent the states and methods to represent the actions (insert coin, press button, and dispense). In each method we put in some conditional statements to define how the machine will behave in the different states. This is how our class will look like.

. . .

public class CandyVendingMachine {

final static int NO_CANDY=0;

final static int NO_COIN=1;

final static int CONTAINS_COIN=2;

final static int DISPENSE=3;

int count;

int state=NO_CANDY;

public CandyVendingMachine(int numberOfCandies){

count=numberOfCandies;

if(count>0) state = NO_COIN;

}

public void insertCoin(){

if(state==CONTAINS_COIN){

System.out.println("Coin already inserted");

}

else if(state==NO_COIN){

state=CONTAINS_COIN;

}

else if(state==NO_CANDY){

System.out.println("No candies available");

}

else if(state==DISPENSE){

System.out.println("Error. System is currently dispensing");

}

}

public void pressButton(){

if(state==CONTAINS_COIN){

state=DISPENSE;

}

else if(state==NO_COIN){

System.out.println("No coin inserted");

}

else if(state==NO_CANDY){

System.out.println("No candies available");

}

else if(state==DISPENSE){

System.out.println("No coin inserted");

}

}

public void dispense(){

if(state==CONTAINS_COIN){

System.out.println("No candies rolled out");

}

else if(state==NO_COIN){

System.out.println("No coin inserted");

}

else if(state==NO_CANDY){

System.out.println("No candies available");

}

else if(state==DISPENSE){

count=count-1;

if(count==0){

state=NO_CANDY;

}

else

state=NO_COIN;

}

}

}

We have ended up with a monolithic class with three action methods, each with a bunch of repeated conditional statements to handle different types of behavior of the machine – A clear violation of the Single Responsibility principle. Now, imagine that a change request comes in to add an action that allows a user to withdraw a coin. We need to open up the class and add a new action method again with a branch of conditional statements. What if a change request for the existing press button action comes in? Say, the machine should roll out two candies when a user presses the button again exactly after a random number of seconds (say after 3 seconds or 5 seconds) that the system decides for each transaction. Again, a whole lot of changes.

Our single monolithic class is very brittle. As business requirements change, the class evolves. Programmers are tempted to add one more if statement for each change in the business requirements. This is what leads to spaghetti code. Left unchecked in a large enterprise system, you get a Big Ball of Mud. This is not a sustainable design pattern, nor is it a path to quality software.

It’s clear our class is not adhering to the Open Close principle. What we need is a system resilient to such changes and this is where the State pattern comes in. By applying the state pattern, we will put each branch of the conditional statements in a separate class. This will enable treating the vending machine states as objects that can vary independently from its peer objects. What we are essentially doing is following the principle of “Encapsulate what varies”.

Participants of the State Pattern

Before we apply the State pattern to our candy vending machine example, we will look at the participants of the pattern. We will define a CandyVendingMachineState class that will contain methods for every operations of the machine. For each state of the machine we will create a separate class. These classes are responsible for defining how the machine should behave in the state that the class represents. As we have four states, we will create four classes and name them NoCoinState, ContainsCoinState, DispensedState, and NoCandyState. We will have the CandyVendingMachine class, but now it will represent information that is mostly fixed. Our refactored CandyVendingMachine class won’t have any conditional statements. Instead it will define interface methods for clients that will delegate to the object representing the current state. We can now summarize the participants of our vending machine example as:

- Context (

CandyVendingMachine): Provides and interface to client to perform some action and delegates state specific requests to the ConcreteState subclass that defines the current state. - State (

CandyVendingMachineState): Is an interface that encapsulates the behavior associated with a particular state of the Context. - ConcreteState subclasses (

NoCoinState,ContainsCoinState,DispensedState, andNoCandyState): Concrete classes that implements a behavior associated with a state of the Context.

Applying the State Pattern

We will now apply the State pattern to the candy vending machine example. Let’s start with the State interface.

CandyVendingMachineState.java

package guru.springframework.gof.state.states;

public interface CandyVendingMachineState {

void insertCoin();

void pressButton();

void dispense();

}

The CandyVendingMachineState interface that we wrote above declares three method representing the operation that can be performed on the machine.

We will next write the ConcreteState subclasses. Let’s start with the NoCoinState class.

NoCoinState.java

package guru.springframework.gof.state.states;

import guru.springframework.gof.state.context.CandyVendingMachine;

public class NoCoinState implements CandyVendingMachineState{

CandyVendingMachine machine;

public NoCoinState(CandyVendingMachine machine){

this.machine=machine;

}

@Override

public void insertCoin() {

machine.setState(machine.getContainsCoinState());

}

@Override

public void pressButton() {

System.out.println("No coin inserted");

}

@Override

public void dispense() {

System.out.println("No coin inserted");

}

@Override

public String toString(){

return "NoCoinState";

}

}

We wrote the NoCoinState class above to implement the CandyVendingMachineState interface. In this class, we maintained a reference to CandyVendingMachine that is initialized through the constructor. We implemented the interface methods to define how the machine should behave when the corresponding operations are carried out and when there is no coin present in the machine. In the insertCoin() method, we changed the current state (No Coin) of the machine to the Contains Coin state represented by the ContainsCoinState class. In the pressButton() and dispense() methods, we simply printed out appropriate messages as obviously our machine will not roll out any candies if no coin is inserted.

Let’s write the other ConcreteState subclasses.

ContainsCoinState.java

package guru.springframework.gof.state.states;

import guru.springframework.gof.state.context.CandyVendingMachine;

public class ContainsCoinState implements CandyVendingMachineState{

CandyVendingMachine machine;

public ContainsCoinState(CandyVendingMachine machine){

this.machine=machine;

}

@Override

public void insertCoin() {

System.out.println("Coin already inserted");

}

@Override

public void pressButton() {

machine.setState(machine.getDispensedState());

}

@Override

public void dispense() {

System.out.println("Press button to dispense");

}

@Override

public String toString(){

return "ContainsCoinState";

}

}

DispensedState.java

package guru.springframework.gof.state.states;

import guru.springframework.gof.state.context.CandyVendingMachine;

public class DispensedState implements CandyVendingMachineState{

CandyVendingMachine machine;

public DispensedState(CandyVendingMachine machine){

this.machine=machine;

}

@Override

public void insertCoin() {

System.out.println("Error. System is currently dispensing");

}

@Override

public void pressButton() {

System.out.println("Error. System is currently dispensing");

}

@Override

public void dispense() {

if(machine.getCount()>0) {

machine.setState(machine.getNoCoinState());

machine.setCount(machine.getCount()-1);

}

else{

System.out.println("No candies available");

machine.setState(machine.getNoCandyState());

}

}

@Override

public String toString(){

return "DispensedState";

}

}

NoCandyState.java

package guru.springframework.gof.state.states;

import guru.springframework.gof.state.context.CandyVendingMachine;

public class NoCandyState implements CandyVendingMachineState{

CandyVendingMachine machine;

public NoCandyState(CandyVendingMachine machine){

this.machine=machine;

}

@Override

public void insertCoin() {

System.out.println("No candies available");

}

@Override

public void pressButton() {

System.out.println("No candies available");

}

@Override

public void dispense() {

System.out.println("No candies available");

}

@Override

public String toString(){

return "NoCandyState";

}

}

As you can observe, the remaining ConcreteState subclasses are structurally same. The difference is how we implemented the behaviors when the machine is in a particular state.

We will next write the Context – the CandyVendingMachine class.

CandyVendingMachine.java

package guru.springframework.gof.state.context;

import guru.springframework.gof.state.states.*;

public class CandyVendingMachine {

CandyVendingMachineState noCoinState;

CandyVendingMachineState noCandyState;

CandyVendingMachineState dispensedState;

CandyVendingMachineState containsCoinState;

CandyVendingMachineState state;

int count;

public CandyVendingMachine(int numberOfCandies){

count=numberOfCandies;

noCoinState=new NoCoinState(this);

noCandyState=new NoCandyState(this);

dispensedState=new DispensedState(this);

containsCoinState=new ContainsCoinState(this);

state = noCoinState;

}

public void refillCandy(int count){

this.count+=count;

this.state=noCoinState;

}

public void ejectCandy(){

if(count!=0){

count--;

}

}

public void insertCoin(){

System.out.println("You inserted a coin.");

state.insertCoin();

}

public void pressButton(){

System.out.println("You have pressed the button.");

state.pressButton();

state.dispense();

}

public CandyVendingMachineState getNoCandyState() {

return noCandyState;

}

public void setNoCandyState(CandyVendingMachineState noCandyState) {

this.noCandyState = noCandyState;

}

public CandyVendingMachineState getNoCoinState() {

return noCoinState;

}

public void setNoCoinState(CandyVendingMachineState noCoinState) {

this.noCoinState = noCoinState;

}

public int getCount() {

return count;

}

public void setCount(int count) {

this.count = count;

}

public CandyVendingMachineState getState() {

return state;

}

public void setState(CandyVendingMachineState state) {

this.state = state;

}

public CandyVendingMachineState getContainsCoinState() {

return containsCoinState;

}

public void setContainsCoinState(CandyVendingMachineState containsCoinState) {

this.containsCoinState = containsCoinState;

}

public CandyVendingMachineState getDispensedState() {

return dispensedState;

}

public void setDispensedState(CandyVendingMachineState dispensedState) {

this.dispensedState = dispensedState;

}

@Override

public String toString(){

String machineDef="Current state of machine "+state +". Candies available "+count;

return machineDef;

}

}

In the CandyVendingMachine class that we wrote above, we defined instance variables for all the four states. In addition we have an instance variable state that will hold the current state of the machine and count that represents the number of candies available in the machine. In the constructor we initialized all the instance variables. We defined two internal methods refillCandy() and ejectCandy() but observe the more important interface methods (that clients will invoke) insertCoin() and pressButton(). In the insertCoin() method, we delegated the call to the insertCoin() method of the current state object. In the pressButton() method we delegated the call first to the pressButton() method and then to the dispense() method of the current state object. The remaining code are the getter and setter methods of the instance variables.

As you can see, in the code that we have written so far, all the ConcreteState subclasses are closed for modifications and our CandyVendingMachine class is open for extension – we can add in a new state. Yes, our example is now adhering to the Open Close principle. Also, we have separate classes for each state where each class is only responsible for how the machine behaves in that state – we are following the Single Responsibility principle.

Let’s now write some test code and see how our candy vending machine operates in different states.

CandyVendingMachineTest.java

package guru.springframework.gof.state.context;

import org.junit.Before;

import org.junit.Test;

import static org.junit.Assert.*;

public class CandyVendingMachineTest {

@Test

public void testCandyVendingMachine() throws Exception {

System.out.println("-----Test 1: Testing machine by inserting coin and pressing button-----");

CandyVendingMachine machine=new CandyVendingMachine(3);

System.out.println(machine);

machine.insertCoin();

System.out.println(machine);

machine.pressButton();

System.out.println(machine);

System.out.println("-----Test 2: Testing machine by pressing button without inserting coin-----");

CandyVendingMachine machine2=new CandyVendingMachine(3);

System.out.println(machine2);

machine2.pressButton();

System.out.println(machine2);

System.out.println("-----Test 3: Testing machine running out of candies-----");

CandyVendingMachine machine3=new CandyVendingMachine(3);

System.out.println(machine3);

machine3.insertCoin();

machine3.pressButton();

machine3.insertCoin();

machine3.pressButton();

machine3.insertCoin();

machine3.pressButton();

machine3.insertCoin();

machine3.pressButton();

System.out.println(machine3);

}

}

In the test class above, from Line 13 – Line 19, we tested how the machine behaves when a user inserts a coin and presses the button. From Line 21 – Line 25, we tested how the machine behaves when a user presses the button without inserting a coin. From Line 27 – Line 38, we tested how the machine behaves when it is out of candies and a user inserts a coin and presses the button.

The output of the test is this.

------------------------------------------------------- T E S T S ------------------------------------------------------- Running guru.springframework.gof.state.context.CandyVendingMachineTest -----Test 1: Testing machine by inserting coin and pressing button----- Current state of machine NoCoinState. Candies available 3 You inserted a coin. Current state of machine ContainsCoinState. Candies available 3 You have pressed the button. Current state of machine NoCoinState. Candies available 2 -----Test 2: Testing machine by pressing button without inserting coin----- Current state of machine NoCoinState. Candies available 3 You have pressed the button. No coin inserted No coin inserted Current state of machine NoCoinState. Candies available 3 -----Test 3: Testing machine running out of candies----- Current state of machine NoCoinState. Candies available 3 You inserted a coin. You have pressed the button. You inserted a coin. You have pressed the button. You inserted a coin. You have pressed the button. You inserted a coin. You have pressed the button. No candies available Current state of machine NoCandyState. Candies available 0 Tests run: 1, Failures: 0, Errors: 0, Skipped: 0, Time elapsed: 0.002 sec - in guru.springframework.gof.state.context.CandyVendingMachineTest

Summary

When you apply the State Pattern, you will always have more classes in your application. Novice programmers may believe this is a bad thing. More classes, more files, more objects to maintain. They may worry this is an extra burden on the computer’s resources. It’s not. The JVM is quite optimized for handling 10’s of thousands of classes.

But avoiding the State Pattern is a sure path to unmaintainable code. Look at the above example with the nested logic. This will become a maintenance nightmare. More time is spent reading code than writing it. Think about when you as a programmer need to modify this code 6 months later. You’ll need to carefully examine it to figure out what it does. And then you’ll need to figure out how to make your changes without breaking other things.

With the State Pattern, your program logic becomes more specific, more encapsulated. Your unit tests are more ‘unity’, which is what you want. When you need lots of unit tests to test the behavior of a single class, your class under test may have a problem. The State Pattern is a classic GoF design pattern because it has stood the test of time. Developers in many different Object Oriented languages have used the State Pattern to produce quality software. Software that is easily maintained as the business requirements grow and change.