Template Method Pattern

“Define the skeleton of an algorithm in an operation, deferring some steps to subclasses. Template Method lets subclasses redefine certain steps of an algorithm without changing the algorithm’s structure.”

Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software

The Behavioral pattern family of the Gang of Four design patterns address responsibilities of objects in an application and how they communicate between them at runtime. The Behavioral patterns that I wrote in this series of GoF patterns are the Command, Chain of Responsibility, Iterator, Mediator, Interpreter, Memento, Observer, State, and Strategy patterns. The Behavioral pattern that I will introduce in this post is the Template Method pattern – a pattern, similar to the Strategy Pattern, that encapsulates algorithms but with a different intent.

Template Method Pattern: Introduction

If you have already gone through my post on Strategy pattern, understanding the Template Method pattern will be easy. If you haven’t done that yet, I recommend you to do so. But, if you want to jump start with Template Method, let me start with a brief introduction on the need of this pattern.

In enterprise applications, some classes need to support multiple similar algorithms to perform some business requirements. A number sorting class that supports multiple sorting algorithms, such as bubble sort, merge sort, and quick sort is an example of such a class. Another example is a data encryption class that encrypts data using different encryption algorithms, such as AES, TripleDES, and Blowfish.

There are several approaches to address such requirements. Novice programmers tend to create a single class with multiple switch case or conditional statements, one each for the supported algorithm. This approach have several inherent drawbacks and quickly leads to tightly coupled and rigid software that is difficult-to-change. It happens mainly because such class designs are blatant violations of the basic Object Oriented tenants and the SOLID design principles – primarily the Open Close and Single Responsibility principles. Imagine the amount of modifications that you will need to do if additional algorithm support are required in the class, or an existing algorithm needs to be discarded or modified.

The other approach is to follow the Object Oriented tenant of “Encapsulate what varies” and move out the algorithms from the host class into separate algorithm-specific classes conforming to a common base interface. The host class through composition maintains a reference to the interface that clients initializes with an object of a concrete algorithm-specific class at runtime. Then clients call an interface method on the host object that delegates the call to the current initialized algorithm-specific object – through what we know as polymorphism. In this approach, the host class have no reference to any concrete algorithm-specific class, resulting in a loosely coupled flexible system. As new requirements pour in, you can add, discard, or modify any algorithm-specific classes without any modification of the host class – a classic implementation of the Open Close principle. Also, this approach leads to more focused unit testing of specific situations. This approach is what the Strategy Pattern is all about.

So how does the Template Method pattern fits in? Also, why do we need it at all if the Strategy Pattern is getting all the right things done? The answer is – The Strategy Pattern is not the optimal solution for all types of algorithms.

Algorithms consist of steps, and some steps can be common across algorithms. Repeating the common steps across the different algorithm-specific classes results in code duplication. In addition, if one of the common steps need modification, we need to modify it across all the implementing classes. Which opens the door to inconsistencies and defects creeping in. A more efficient approach is to put the commonality (the common steps) into an abstract base class. In the abstract class, we have a single interface method that clients call. This method makes calls in a specific order to the methods implementing the steps of the algorithm. For the common steps, we have their implementations in the abstract base class itself. The algorithm-specific subclasses extending the abstract base class will inherit those common steps. For the algorithm-specific (primitive) steps, we mark them as abstract. The algorithm-specific subclasses override the primitive steps with their own implementations.

This is the Template Method Pattern. In a nutshell, this pattern defines the skeleton of an algorithm as an abstract class, allowing its subclasses to provide concrete behavior. The interface method in the abstract class that clients call is the template method – In simple terms, a method that defines an algorithm as a series of steps.

Let’s look how a template method works in an abstract base class.

. . .

public abstract class AlgorithmSkeleton {

public void execute() {

stepOne();

stepTwo();

stepThree();

if(doClientRequire()){

stepFour();

}

}

final void stepOne() {

System.out.println( "stepOne performed" );

}

abstract void stepTwo();

abstract void stepThree();

final void stepFour() {

System.out.println( "stepFour performed" );

}

boolean doClientRequire () {

return true;

}

}

In the AlgorithmSkeleton class above, we wrote the execute() method, a template method that makes a series of method calls in a specific order to perform the steps of an algorithm. The template method ensures that the algorithm’s structure remains unchanged, while allowing subclasses to provide implementation of the algorithm-specific steps. For more clarity, examine the individual methods. You will observe that we provided default implementation for the stepOne() and stepFour() methods. These are the steps that will be common to all algorithm-specific sub classes. We declared them final because we don’t want the subclasses to override them and provide some other implementations. We declared stepTwo() and stepThree() as abstract. They are algorithm-specific (primitive) methods that subclasses need to implement in their own specific way. Things get interesting with the doClientRequire() method. This method returns a true boolean value and we have deliberately not declared it final to allow subclasses to optionally override it. Such methods are called hook methods. Hook methods are useful in the way that it allows subclasses to “hook into” the algorithm at various points, if they wish to. A hook method can be empty or return a default value as our doClientRequire() hook method does.

Let’s look at a concrete algorithm-specific subclass.

. . .

public class Algorithm1Impl extends AlgorithmSkeleton {

@Override

public void stepTwo(){

System.out.println("Algorithm1Impl: Step 2 performed");

}

@Override

public void stepThree(){

System.out.println("Algorithm1Impl: Step 3 performed");

}

}

The Algorithm1Impl class extends the AlgorithmSkeleton abstract class and provides implementation of the abstract methods of AlgorithmSkeleton. We have not overridden the hook method, because as of now we don’t need our Algorithm1Impl to “hook into” the algorithm. We will have a deeper look at the usage of hook methods a bit later.

Template methods lead to an inverted control structure that’s sometimes referred to as the Hollywood principle that states “Don’t call us, we’ll call you“. The Hollywood principle prevents “Dependency rot” that occurs whenever low-level components depends on high level components. In the Template Method pattern, it’s the other way around – the abstract base class calls the operations of a subclass and not the other way around. This is apparent in our high-level class AlgorithmSkeleton that essentially tells the low-level Algorithm1Impl class “Don’t call us, we’ll call you”.

Participants of the Template Method Pattern

I explained how Template Method works and the benefits it provides. Like any other pattern, the challenge is to identify scenarios in applications where this pattern should be applied. Let me explain in terms of a real world analogy of a pizza maker example. Consider we need to model a pizza maker that makes different types of pizzas, such as takeaway veg and non-veg pizzas and also pizzas served to customers walking into the restaurant. In our example, we can consider different types of pizza making as different algorithms. For example, different algorithms to make takeaway veg and non-veg pizzas. Also, a different algorithm to make specialty pizzas served in the restaurant.

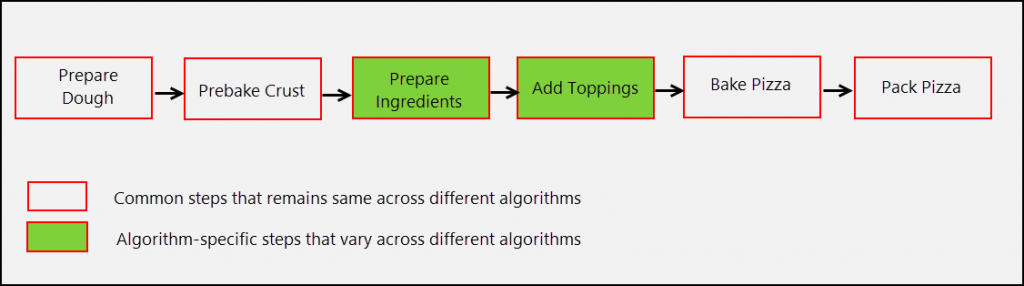

The immediate next task is to identify the steps of the algorithm and distinguish the common and algorithm-specific steps. This is how the steps can be identified on a drawing board.

As you can see in the figure above, the Prepare Dough, Prebake Crust, Bake Pizza, and Pack Pizza steps will be common across all pizza making algorithms. Our restaurant wants to maintain standards and so does not allow the different pizza maker algorithms to have their own way of preparing dough, prebaking crust, baking pizza, and packing them. The Prepare Ingredients and Add Toppings are algorithm specific. This is apparent because Prepare Ingredients for veg pizzas will obviously be different from non-veg pizzas. Similar is the case for the Add Toppings step.

As we have now identified the steps of the pizza making algorithms, we will create an abstract base class with a template method that calls the algorithm steps. In the abstract base class, we will provide implementations of the common steps and mark the algorithm-specific steps (Prepare Ingredients and Add Toppings) as abstract. Let’s name the abstract class – PizzaMaker. Now our algorithm-specific classes, which we will name as VegPizzaMaker, NonVegPizzaMaker, and InHouseAssortedPizzaMaker will extend the abstract PizzaMaker class and inherit the implementations of the common steps. Our algorithm-specific classes need to only override the abstract steps (Prepare Ingredients and Add Toppings) and provide specific implementations.

Based on our pizza maker example, we can identify the participants of the Template Method pattern as:

- AbstractClass (

PizzaMaker): Is an abstract class that contains a template method defining the skeleton of an algorithm. The template method calls methods to perform the steps of an algorithm. The methods can be both common across and specific to different algorithm implementations. - ConcreteClass (

VegPizzaMaker,NonVegPizzaMaker, andInHouseAssortedPizzaMaker): Are concrete subclasses of AbstractClass that implements the operations to carry out the algorithm-specific primitive steps.

Applying the Template Method Pattern

As we have identified and distinguished the algorithm steps and the participants of the pizza maker example, we can start writing code to apply the Template Method pattern. We will start with the AbstractClass – PizzaMaker.

Pizzamaker.java

package guru.springframework.gof.templatemethod;

public abstract class PizzaMaker {

public void makePizza() {

preparePizzaDough();

preBakeCrust();

prepareIngredients();

addToppings();

bakePizza();

if (customerWantsPackedPizza()) {

packPizza();

}

}

final void preparePizzaDough() {

System.out.println("Preparing pizza dough with plain flour, dried yeast, caster sugar, salt, olive oil, and warm water.");

}

final void preBakeCrust() {

System.out.println("Pre baking crust at 325 F for 3 minutes.");

}

abstract void prepareIngredients();

abstract void addToppings();

void bakePizza() {

System.out.println("Baking pizza at 400 F for 12 minutes.");

}

void packPizza() {

System.out.println("Packing pizza in pizza delivery box.");

}

boolean customerWantsPackedPizza() {

return true;

}

}

In the PizzaMaker class above, we wrote the makePizza() template method that calls the various methods implementing the steps of pizza making. We provided implementation of the common preparePizzaDough(), preBakeCrust(), bakePizza(), and packPizza() methods and declared the prepareIngredients() and addToppings() methods as abstract for the subclasses to implement. The customerWantsPackedPizza() method that we wrote is a hook method that returns a default true value. While writing the subclasses, we will identify which subclass needs to “hook into” the algorithm by overriding the hook method.

We will next write the ConcreteClasses : The VegPizzaMaker, NonVegPizzaMaker, and InHouseAssortedPizzaMaker concrete subclasses.

VegPizzaMaker.java

package guru.springframework.gof.templatemethod;

public class VegPizzaMaker extends PizzaMaker {

@Override

public void prepareIngredients() {

System.out.println("Preparing mushroom, tomato slices, onions, and fresh basil leaves.");

}

@Override

public void addToppings() {

System.out.println("Adding mozzerella cheese and tomato sauce along with ingredients to crust.");

}

}

NonVegPizzaMaker.java

package guru.springframework.gof.templatemethod;

public class NonVegPizzaMaker extends PizzaMaker {

@Override

public void prepareIngredients() {

System.out.println("Preparing chicken ham, onion, chicken sausages, and smoked chicken");

}

@Override

public void addToppings() {

System.out.println("Adding cheese, pepper jelly, and BBQ sauce along with ingredients to crust.");

}

}

InHouseAssortedPizzaMaker.java

package guru.springframework.gof.templatemethod;

public class InHouseAssortedPizzaMaker extends PizzaMaker {

@Override

public void prepareIngredients() {

System.out.println("Preparing sweet corns,chicken sausage, green chillies, and onions.");

}

@Override

public void addToppings() {

System.out.println("Adding cheddar cheese and bechamel sauce along with ingredients to crust.");

}

@Override

public boolean customerWantsPackedPizza() {

return false;

}

}

All the subclasses we wrote above extend the abstract PizzaMaker class and provides their own implementation of the prepareIngredients() and addToppings() methods. It’s in the InHouseAssortedPizzaMaker class, that we have overridden the customerWantsPackedPizza() hook method to return false – We obviously don’t want pizzas to be served to walk in customers of the restaurant in packed delivery boxes.

We will test our example by writing this test class.

PizzaMakerTest,java

package guru.springframework.gof.templatemethod;

import org.junit.Test;

import static org.junit.Assert.*;

public class PizzaMakerTest {

@Test

public void testMakePizza() throws Exception {

System.out.println("-----Making Veg Pizza-----");

PizzaMaker vegPizzaMaker = new VegPizzaMaker();

vegPizzaMaker.makePizza();

System.out.println("-----Making Non Veg Pizza-----");

PizzaMaker nonVegPizzaMaker = new NonVegPizzaMaker();

nonVegPizzaMaker.makePizza();

System.out.println("-----Making In-House Assorted Pizza-----");

PizzaMaker inHouseAssortedPizzaMaker = new InHouseAssortedPizzaMaker();

inHouseAssortedPizzaMaker.makePizza();

}

}

In the test classes we instantiated each of the subclasses of PizzaMaker and made calls to the makePizza() template method on them.

The output of the test is this.

------------------------------------------------------- T E S T S ------------------------------------------------------- Running guru.springframework.gof.templatemethod.PizzaMakerTest -----Making Veg Pizza----- Preparing pizza dough with plain flour, dried yeast, caster sugar, salt, olive oil, and warm water. Pre baking crust at 325 F for 3 minutes. Preparing mushroom, tomato slices, onions, and fresh basil leaves. Adding mozzerella cheese and tomato sauce along with ingredients to crust. Baking pizza at 400 F for 12 minutes. Packing pizza in pizza delivery box. -----Making Non Veg Pizza----- Preparing pizza dough with plain flour, dried yeast, caster sugar, salt, olive oil, and warm water. Pre baking crust at 325 F for 3 minutes. Preparing chicken ham, onion, chicken sausages, and smoked chicken Adding cheese, pepper jelly, and BBQ sauce along with ingredients to crust. Baking pizza at 400 F for 12 minutes. Packing pizza in pizza delivery box. -----Making In-House Assorted Pizza----- Preparing pizza dough with plain flour, dried yeast, caster sugar, salt, olive oil, and warm water. Pre baking crust at 325 F for 3 minutes. Preparing sweet corns,chicken sausage, green chillies, and onions. Adding cheddar cheese and bechamel sauce along with ingredients to crust. Baking pizza at 400 F for 12 minutes. Tests run: 1, Failures: 0, Errors: 0, Skipped: 0, Time elapsed: 0.002 sec - in guru.springframework.gof.templatemethod.PizzaMakerTest

In the output, observe that all the concrete subclasses have inherited the common steps implemented in the abstract PizzaMaker base class. The subclasses only performs the algorithm-specific steps of preparing pizza and adding toppings. Also notice that the InHouseAssortedPizzaMaker implementation does not performed the step of packing pizza, as it “hooks into” the algorithm to specify that no packing is required. Recall the InHouseAssortedPizzaMaker class we wrote earlier where we had overridden the customerWantsPackedPizza() hook method to return false.

Summary

As I mentioned earlier, the Strategy Pattern is similar to the Template Method Pattern except in its granularity. Template Method uses inheritance to vary part of an algorithm while Strategies use delegation to vary the entire algorithm. In addition to adhering to the SOLID Open Close, and Single Responsible principles, Template Method puts in use the Hollywood principle – a specialized form of the Dependency Inversion principle. Dependency Inversion advocates working with abstractions instead of concrete classes. In Template Method, the Hollywood principle does it through a technique of creating designs with hooks that allows low-level components to interoperate with high-level components while preventing any direct dependencies.

Template Method is extensively used in both Java SE and Java EE APIs. The non-abstract methods of InputStream, OutputStream, Reader, and Writer of java.io are template methods. Also, the non-abstract methods of AbstractList, AbstractSet, and AbstractMap classes of java.util are template methods. In Java EE, all the doXXX() methods, of HttpServlet are template methods. These methods by default sends a HTTP 405 ‘Method Not Allowed’ error to the response. You’re free to implement none or any of those template methods.

While developing Enterprise Application using the Spring Framework, you will encounter several template methods built in the framework. The handleRequestInternal() method of the abstract AbstractController class is one such template method. In Spring applications, when you need to implement some common logic, with some subclass specific logic interleaved with it, use the Template Method pattern to reduce code duplication and code maintenance nightmares in your application. After all, it’s a proven solution and part of the classic GoF patterns.