Visitor Pattern

“Represent an operation to be performed on the elements of an object structure. Visitor lets you define a new operation without changing the classes of the elements on which it operates.”

Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software

The Behavioral pattern family of the Gang of Four design patterns address responsibilities of objects in an application and how they communicate between them at runtime. The other GoF Behavioral patterns that I wrote in this series of GoF patterns are:

- Chain of Responsibility: Delegates commands to a chain of processing objects.

- Command: Creates objects which encapsulate actions and parameters.

- Interpreter: Implements a specialized language.

- Iterator: Accesses the elements of an object sequentially without exposing its underlying representation.

- Mediator: Allows loose coupling between classes by being the only class that has detailed knowledge of their methods.

- Memento: Provides the ability to restore an object to its previous state.

- Observer: Is a publish/subscribe pattern which allows a number of observer objects to see an event.

- State: Allows an object to alter its behavior when it’s internal state changes.

- Strategy: Allows one of a family of algorithms to be selected on-the-fly at runtime.

- Template Method: Defines the skeleton of an algorithm as an abstract class, allowing its subclasses to provide concrete behavior.

The final Behavioral pattern that I will discuss in this post is the Visitor pattern – A pattern that decouples the algorithm from an object structure on which it operates.

Visitor Pattern: Introduction

When going into enterprise application development, you will be working more and more with object structures. Such structures can range from a collection of objects, object inheritance trees, to complex structures comprising of a composite implemented using the Composite structural pattern. As you start working, you will be adding operations to the elements of such structures and distributing the operations across the other elements of the structure.

This complexity can quickly lead to a messy system that’s hard to understand, maintain, and change. Imagine, you or some other programmers later need to change the class of one such element to address some new requirements. Initially, understanding the code itself is a big challenge. Think in terms of understanding a class with over thousand lines of code. I’ve seen this type of class too many times in legacy code. One large class, with just one public method, and over one thousand lines of code.

It’s extremely time consuming to just understand what the class is trying to do. The smallest of changes need to be delicately thought out to ensure you’re not breaking things.

Let’s start with an example of a mail client configurator application. The requirements state that the application should allow users to configure and use the open source Opera and Squirell mail clients in Windows and Mac environments. Sounds simple – So let’s start coding by creating an interface containing the operations of the mail clients and the subclasses, one each for the mail clients.

This is how our interface looks like.

. . .

public interface MailClient {

void sendMail(String[] mailInfo);

void receiveMail(String[] mailInfo);

boolean configureForMac();

boolean configureForWindows();

}

The subclasses representing the mail clients will be similar to the following classes.

. . .

public class OperaMailClient implements MailClient {

@Override

public void sendMail(String[] mailInfo) {

System.out.println(" OperaMailClient: Sending mail");

}

@Override

public void receiveMail(String[] mailInfo) {

System.out.println(" OperaMailClient: Receiving mail");

}

@Override

public boolean configureForMac() {

System.out.println("Configuration of Opera mail client for Mac complete");

return true;

}

@Override

public boolean configureForWindows() {

System.out.println("Configuration of Opera mail client for Windows complete");

return true;

}

. . .

public class SquirrelMailClient implements MailClient {

@Override

public void sendMail(String[] mailInfo) {

System.out.println("SquirrelMailClient: Sending mail");

}

@Override

public void receiveMail(String[] mailInfo) {

System.out.println("SquirrelMailClient: Receiving mail");

}

@Override

public boolean configureForMac() {

System.out.println("Configuration of Squirrel mail client for Mac complete");

return true;

}

@Override

public boolean configureForWindows() {

System.out.println("Configuration of Squirrel mail client for Windows complete");

return true;

}

}

A client can program against the interface and call one of the required configureForXX() methods to configure a mail client for a particular environment, something similar to this.

. . .

public class MailClientTest {

@Test

public void testConfigureMailClientForDifferentEnvironments() throws Exception {

MailClient operaMailClient=new OperaMailClient();

assertTrue(operaMailClient.configureForMac());

assertTrue(operaMailClient.configureForWindows());

MailClient squirrelMailClient=new SquirrelMailClient();

assertTrue(squirrelMailClient.configureForMac());

assertTrue(squirrelMailClient.configureForWindows());

}

}

The output of the test will be this.

Configuration of Opera mail client for Mac complete Configuration of Opera mail client for Windows complete Configuration of Squirrel mail client for Mac complete Configuration of Squirrel mail client for Windows complete

The design of our object structure seems simple enough and you may be wondering why we need another pattern because our code is getting all the right things done. Yes, we have functional code. But the code is not maintainable. Changing requirements are difficult to implement.

Imagine that a new requirement comes in to provide support for Linux. We not only need to update the MailClient interface with a new configureForLinux() method, we will also need to update each of the concrete subclasses to provide implementation of the new configureForLinux() method. Things might not appear as bad in the current structure as we have only two concrete classes, but consider providing configuration support on Linux for more than 30 mail clients that our application supports.

You can see how evolving requirements will cause our current design to eventually become unmaintainable.

What is the alternative? How do we handle such designs? One answer is for us to follow the Divide and Conquer strategy by applying the Visitor pattern. By using the Visitor pattern, you can separate out an algorithm present in the elements of an object structure to another object, known as a visitor. This is exactly what the GoF means in the first sentence of the Visitor patterns’ intent “Represent an operation to be performed on the elements of an object structure.”

A practical result of this separation is the ability to add new operations to the elements of an object structure without modifying it – One way to follow the Open Closed principle. Again, this is exactly what the GoF means when it says in the second sentence of the intent – “Visitor lets you define a new operation without changing the classes of the elements on which it operates.”

Participants of the Visitor Pattern

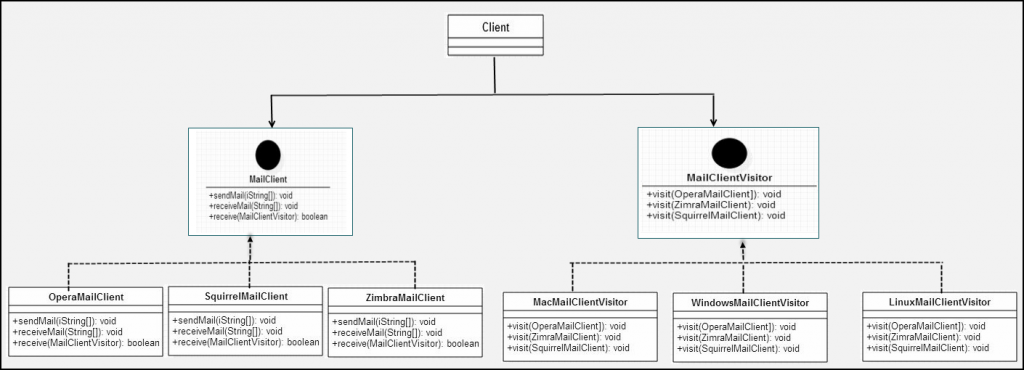

To understand how the Visitor pattern works, let’s continue with the mail client configurator application. By now, we have realized that the design mistake we made was having the configuration algorithm embedded in the elements of the object structure. So, as a solution we will separate out the configuration algorithms from the elements to visitors. The elements of our object structure will remain the same – we will have the MailClient interface and concrete subclasses for configuring and using different mail clients. Let’s model three subclasses: OperaMailClient, SquirrelMailClient, and ZimbraMailClient. What will now differ is the operations that goes into the interface that the subclasses will implement. We will replace all the configureForXX() methods in the MailClient interface with a single visit() method that will take as input a vistor object. More on this later.

We also need to create the visitors. We need a visitor interface, say MailClientVisitor containing a visit() methods to perform operations on each of the mail clients we have. Concrete visitor classes override the visit() methods of MailClientVisitor to implement the mail client configuration algorithms. Let’s name the visitor classes MacMailClientVisitor, WindowsMailClientVisitor, and LinuxMailClientVisitor.

This is how our class diagram looks like after applying the Visitor pattern.

From our class diagram above, we can summarize the participants of the Visitor pattern as:

- Element (

MailClient): Is an interface that containsaccept()method that takes a visitor as an argument. - ConcreteElement (

OperaMailClient,SquirrelMailClient, andZimbraMailClient): Implements theaccept()method declared in Element. - Visitor (

MailClientVisitor): Is an interface that declares avisit()method for each class of ConcreteElement in the object structure. - ConcreteVisitor (

MacMailClientVisitor,WindowsMailClientVisitor, andLinuxMailClientVisitor): Are the concrete classes that implements each method declared by Visitor.

Applying the Visitor Pattern

We will now write the code to apply the Visitor pattern to the mail client configurator application. Let’s start with the Element – the MailClient interface

MailClient.java

package guru.springframework.gof.visitor.structure;

import guru.springframework.gof.visitor.visitors.MailClientVisitor;

public interface MailClient {

void sendMail(String[] mailInfo);

void receiveMail(String[] mailInfo);

boolean accept(MailClientVisitor visitor);

}

The MailClient interface above declares the regular operations to send and receive mails through the sendMail() and receiveMail() methods. But what’s important to observe is the visit() method that accepts a Visitor object, which in our example is a type of MailClientVisitor.

Next, we will write the concrete elements (OperaMailClient, SquirrelMailClient, and ZimbraMailClient).

OperaMailClient.java

package guru.springframework.gof.visitor.structure;

import guru.springframework.gof.visitor.visitors.MailClientVisitor;

public class OperaMailClient implements MailClient{

@Override

public void sendMail(String[] mailInfo) {

System.out.println(" OperaMailClient: Sending mail");

}

@Override

public void receiveMail(String[] mailInfo) {

System.out.println(" OperaMailClient: Receiving mail");

}

@Override

public boolean accept(MailClientVisitor visitor) {

visitor.visit(this);

return true;

}

}

SquirrelMailClient.java

package guru.springframework.gof.visitor.structure;

import guru.springframework.gof.visitor.visitors.MailClientVisitor;

public class SquirrelMailClient implements MailClient{

@Override

public void sendMail(String[] mailInfo) {

System.out.println(" SquirrelMailClient: Sending mail");

}

@Override

public void receiveMail(String[] mailInfo) {

System.out.println(" SquirrelMailClient: Receiving mail");

}

@Override

public boolean accept(MailClientVisitor visitor) {

visitor.visit(this);

return true;

}

}

ZimbraMailClient.java

package guru.springframework.gof.visitor.structure;

import guru.springframework.gof.visitor.visitors.MailClientVisitor;

public class ZimbraMailClient implements MailClient{

@Override

public void sendMail(String[] mailInfo) {

System.out.println(" ZimbraMailClient: Sending mail");

}

@Override

public void receiveMail(String[] mailInfo) {

System.out.println(" ZimbraMailClient: Receiving mail");

}

@Override

public boolean accept(MailClientVisitor visitor) {

visitor.visit(this);

return true;

}

}

In all the concrete element classes above, we implemented the accept() method, in addition to the sendMail() and receiveMail() methods. In the accept() method, we called the visit() method on the visitor passed as an argument to accept(). While calling the visit() method, we passed this (this concrete element object) as the method parameter. We did it for all the concrete element classes. At runtime a visitor calls the visit() method on a concrete element, which calls back into the visitor passing itself – a mechanism called double dispatch.

Unlike programming languages like Common Lisp, double dispatch is not natively supported by modern OO programming languages including Java. The Visitor pattern allows you to simulate double dispatch in Java. I will cover how it is done once we finish writing the visitors.

Going back to the concrete element classes, we replaced the hard coded configureForXX() methods with the accept() method, thereby removing the configuration algorithms out from the classes. The consequence? – We can now plug in a new mail client configurator, say a configurator class for Mozilla Thunderbird to our application without disturbing the existing structure. All we need to do is write a class, say MozillaThunderbirdMailClient, implement the accept() method of MailClient, and we are ready to go.

Let’s now write the visitors starting with the MailClientVisitor interface.

MailClientVisitor.java

package guru.springframework.gof.visitor.visitors;

import guru.springframework.gof.visitor.structure.OperaMailClient;

import guru.springframework.gof.visitor.structure.SquirrelMailClient;

import guru.springframework.gof.visitor.structure.ZimbraMailClient;

public interface MailClientVisitor {

void visit(OperaMailClient mailClient);

void visit(SquirrelMailClient mailClient);

void visit(ZimbraMailClient mailClient);

}

In the MailClientVisitor interface above, we have visit() methods corresponding to each of the mail clients (Concrete elements), we wrote earlier.

Now, we can write the concrete visitors.

WindowsMailClientVisitor.java

package guru.springframework.gof.visitor.visitors;

import guru.springframework.gof.visitor.structure.OperaMailClient;

import guru.springframework.gof.visitor.structure.SquirrelMailClient;

import guru.springframework.gof.visitor.structure.ZimbraMailClient;

public class WindowsMailClientVisitor implements MailClientVisitor{

@Override

public void visit(OperaMailClient mailClient) {

System.out.println("Configuration of Opera mail client for Windows complete");

}

@Override

public void visit(SquirrelMailClient mailClient) {

System.out.println("Configuration of Squirrel mail client for Windows complete");

}

@Override

public void visit(ZimbraMailClient mailClient) {

System.out.println("Configuration of Zimbra mail client for Windows complete");

}

}

MacMailClientVisitor.java

package guru.springframework.gof.visitor.visitors;

import guru.springframework.gof.visitor.structure.OperaMailClient;

import guru.springframework.gof.visitor.structure.SquirrelMailClient;

import guru.springframework.gof.visitor.structure.ZimbraMailClient;

public class MacMailClientVisitor implements MailClientVisitor{

@Override

public void visit(OperaMailClient mailClient) {

System.out.println("Configuration of Opera mail client for Mac complete");

}

@Override

public void visit(SquirrelMailClient mailClient) {

System.out.println("Configuration of Squirrel mail client for Mac complete");

}

@Override

public void visit(ZimbraMailClient mailClient) {

System.out.println("Configuration of Zimbra mail client for Mac complete");

}

}

LinuxMailClientVisitor.java

package guru.springframework.gof.visitor.visitors;

import guru.springframework.gof.visitor.structure.OperaMailClient;

import guru.springframework.gof.visitor.structure.SquirrelMailClient;

import guru.springframework.gof.visitor.structure.ZimbraMailClient;

public class LinuxMailClientVisitor implements MailClientVisitor{

@Override

public void visit(OperaMailClient mailClient) {

System.out.println("Configuration of Opera mail client for Linux complete");

}

@Override

public void visit(SquirrelMailClient mailClient) {

System.out.println("Configuration of Squirrel mail client for Linux complete");

}

@Override

public void visit(ZimbraMailClient mailClient) {

System.out.println("Configuration of Zimbra mail client for Linux complete");

}

}

All the concrete visitors, WindowsMailClientVisitor, MacMailClientVisitor, and LinuxMailClientVisitor that we wrote above implement the visit() methods. For the purpose of illustration, we have just printed out some messages, but in a real-world application, the algorithms for configuring different mail clients for a particular environment will go in these visit() methods.

Let’s revisit our discussion on double dispatch in the Visitor pattern. Carefully observe that in our current design, different visitors can visit the same concrete element. For example, MacMailClientVisitor, WindowsMailClientVisitor, and LinuxMailClientVisitor are different visitors that can visit the concrete element, OperaMailClient. Similarly, different concrete elements can be visited by the same visitor. For example, OperaMailClient, SquirellMailClient, and ZimbraMail are different concrete elements that can be visited by MacMailClientVisitor. Therefore, a named operation performed using the Visitor pattern depends on the visitor and the concrete element (double dispatch). This is in contrast to what happens when we perform a regular method invocation in Java (single dispatch). In single dispatch, method invocation depends on a single criteria: The class of the object on which the method needs to be invoked.

We will now write a test class to test our mail client configurator application.

MailClientVisitorTest.java

package guru.springframework.gof.visitor.visitors;

import guru.springframework.gof.visitor.structure.OperaMailClient;

import guru.springframework.gof.visitor.structure.SquirrelMailClient;

import guru.springframework.gof.visitor.structure.ZimbraMailClient;

import org.junit.Before;

import org.junit.Test;

import static org.junit.Assert.*;

public class MailClientVisitorTest {

private MacMailClientVisitor macVisitor;

private LinuxMailClientVisitor linuxVisitor;

private WindowsMailClientVisitor windowsVisitor;

private OperaMailClient operaMailClient;

private SquirrelMailClient squirrelMailClient;

private ZimbraMailClient zimbraMailClient;

@Before

public void setup(){

macVisitor=new MacMailClientVisitor();

linuxVisitor=new LinuxMailClientVisitor();

windowsVisitor=new WindowsMailClientVisitor();

operaMailClient = new OperaMailClient();

squirrelMailClient=new SquirrelMailClient();

zimbraMailClient=new ZimbraMailClient();

}

@Test

public void testOperaMailClient() throws Exception {

System.out.println("-----Testing Opera Mail Client for different environments-----");

assertTrue(operaMailClient.accept(macVisitor));

assertTrue(operaMailClient.accept(linuxVisitor));

assertTrue(operaMailClient.accept(windowsVisitor));

}

@Test

public void testSquirrelMailClient() throws Exception {

System.out.println("\n-----Testing Squirrel Mail Client for different environments-----");

assertTrue(squirrelMailClient.accept(macVisitor));

assertTrue(squirrelMailClient.accept(linuxVisitor));

assertTrue(squirrelMailClient.accept(windowsVisitor));

}

@Test

public void testZimbraMailClient() throws Exception {

System.out.println("\n-----Testing Zimbra Mail Client for different environments-----");

assertTrue(zimbraMailClient.accept(macVisitor));

assertTrue(zimbraMailClient.accept(linuxVisitor));

assertTrue(zimbraMailClient.accept(windowsVisitor));

}

}

In the test class above we used JUnit to test the different mail client configurator classes. If you are new to JUnit, you can look at the series of post that I wrote on JUnit here.

The output on running the test is this.

------------------------------------------------------- T E S T S ------------------------------------------------------- Tests run: 1, Failures: 0, Errors: 0, Skipped: 0, Time elapsed: 0.005 sec - in guru.springframework.gof.templatemethod.PizzaMakerTest Running guru.springframework.gof.visitor.visitors.MailClientVisitorTest -----Testing Opera Mail Client for different environments----- Configuration of Opera mail client for Mac complete Configuration of Opera mail client for Linux complete Configuration of Opera mail client for Windows complete -----Testing Squirrel Mail Client for different environments----- Configuration of Squirrel mail client for Mac complete Configuration of Squirrel mail client for Linux complete Configuration of Squirrel mail client for Windows complete -----Testing Zimbra Mail Client for different environments----- Configuration of Zimbra mail client for Mac complete Configuration of Zimbra mail client for Linux complete Configuration of Zimbra mail client for Windows complete Tests run: 3, Failures: 0, Errors: 0, Skipped: 0, Time elapsed: 0.002 sec - in guru.springframework.gof.visitor.visitors.MailClientVisitorTest Running guru.springframework.gof.visitor.withoutvisitor.MailClientTest Configuration of Opera mail client for Mac complete Configuration of Opera mail client for Windows complete Configuration of Squirrel mail client for Mac complete Configuration of Squirrel mail client for Windows complete Tests run: 1, Failures: 0, Errors: 0, Skipped: 0, Time elapsed: 0.002 sec - in guru.springframework.gof.visitor.withoutvisitor.MailClientTest

Summary

If you’ve found the Visitor pattern complex, as compared to the other GoF behavioral patterns, don’t worry because you’re not alone. The Visitor pattern is often conceived as overly complex. It stems from the fact that a visitor can visit a collection of different object, a composite created by applying the Composite pattern, or an inheritance tree. A clear understanding and careful decision is required before using Visitor, else it can make your code unnecessarily complex. But in the right situations, the Visitor Pattern can be an elegant solution to complex situations.

When it comes to the Spring Framework, you will observe that Spring implements the Visitor design pattern with org.springframework.beans.factory.config.BeanDefinitionVisitor for beans configuration. A BeanDefinitionVisitor is used to parse bean metadata and resolve them into String or Object that are set into BeanDefinition instances associated with analyzed bean. Obviously, the requirements for Spring’s IoC container are complex. You can examine the related Spring Framework code to see how the Visitor pattern has provided an elegant solution to this complex use case.